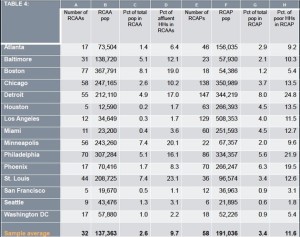

I’ve been offline with respect to this blog for a while, completing an article on the historical relationship of color-blind racial ideology and political geography in metro Atlanta, arguing that the contemporary movement for secession in north Fulton County is part of a long series of maneuvers to manipulate political geography to favor the interests of north Fulton residents and limit the ability of African American voters and officials in the rest of the county to influence them.

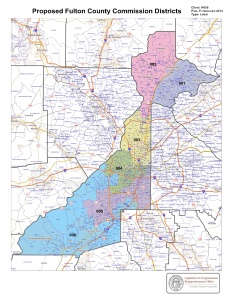

One of the things I like about the kind of history I practice is that it tends to blur the distinction between past and present as objects of inquiry. It’s exciting when the history you write is still unfolding. A major event in that unfolding just happened in a recent state legislative hearing in Atlanta, with the introduction of HB 171, a bill sponsored by six north Fulton County Republicans to redistrict and reapportion the Fulton County Commission. The commission, as Bill Pendered reports in the Saporta Report (invaluable for coverage of metro Atlanta and the General Assembly), now has two at-large seats (including the chair) and five district seats. One seat lies entirely in the city of Atlanta, while two cover south Fulton County, one covers the Buckhead area in north Atlanta and parts of north Fulton, and the fifth covers far north Fulton County. The new districting would eliminate the second at-large district, extend the Buckhead district south to Midtown, and divide North Fulton among two Commission districts.

Courtesy GA Legislative and Congressional Reapportionment Office, 2013

There are some legitimate reasons for eliminating the second at-large seat; creating a sixth district would make all of the districts somewhat smaller and, in principle, more responsive. It would also eliminate an at-large seat could be considered redundant, since the commission chair currently answers to all of the voters. In the abstract, redistricting Fulton County is a fine idea.

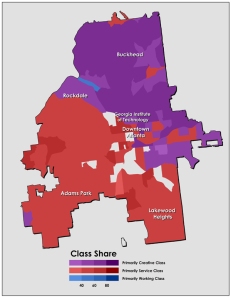

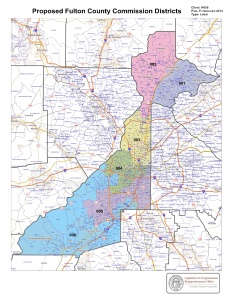

The problem, of course, as J. Morgan Kousser ably demonstrates in a legal history of voting rights and racially-driven redistricting, lies in the fact that districts are drawn not to serve abstract principles but real-world political interests. This graphic of the current commission district, which includes the headshots of the current commissioners, might offer a bit of perspective:

Map and Portraits from Fulton County Commission

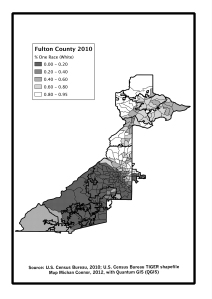

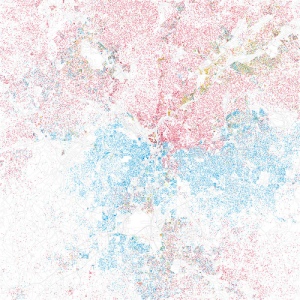

If the concern were for making the commissioners more responsive and accountable, why stop at eliminating only the at-large District 2? Why not make all seven seats district-based and have the members elect a chair? The answer of course is political advantage. In effect, the bill trades a seat elected by a majority-minority county (now held by Democrat Robb Pitts) for a district election with white supermajority in the electorate. Since the geography of all of the Commission districts would change, there is no single “new district” being created. But the percentages of African Americans of voting age in each of the three proposed northern districts ranges from 10.7 to 15.4%, while the percentage of Hispanics of voting age in each ranges from 7.9 to 10.2%. The proposed district with the largest share of minorities of voting age would be the new District 2, covering Roswell and Milton and parts of Alpharetta. While a quarter of this district’s voting age population would be a member of these two minority groups, minorities would be well overmatched by a solidly Republican white electorate. And, while the new District 3 would essentially extend the current District 4 southward, it would do so as Pendered notes, only to “10th Street. Tenth Street is at, or near, the historic – and often unremarked in public – dividing line between the county’s black and white communities.”

To put this in a context of electoral math, 71% of the voting power on the Commission, and 60% of the district-based vote, is currently held by black Democrats. Fulton County gave about 67% of its vote to Barack Obama in the 2012 election. In other words, the current commission apportionment, even with two at-large seats, only moderately inflates the power of voters who favored a black moderate Democrat in a presidential election over a corporate Republican with an arch-conservative running mate. It’s a very rough proxy for local voting preferences, but I think it works OK for quick-and-dirty analytical purposes (and, at risk of making a racially reductive argument, see illustration 2 above).

The redistricting plan, however, would split the district-based votes 50-50, and ensure that north Fulton Republicans would control no less than 42% of the overall commission votes–and 57% if they could win the chair. If we use countywide Romney-voting as our yardstick, north Fulton Republicans win under the new deal even if they lose. And, although it would be difficult for white north Fulton Republicans to win a countywide race for commission chair, it wouldn’t be impossible. A Republican has chaired the commission as recently as Karen Handel’s tenure (which ended in 2007, shortly before an unsuccessful primary run for governor and a now-infamous tenure with the Susan G. Komen Foundation), and with three absolutely secure seats in Buckhead and north Fulton, the party would be able to concentrate its funding on one must-win countywide race, rather than two.

It’s not a coincidence that HB 347, another bill being sponsored by virtually the same group of north Fulton House Republicans, seeks to reorganize the Fulton County Board of Elections. Whereas the County Commission now appoints the election commissioners, under proposed legislation, the Fulton County delegation of the legislature would appoint two Democrats, two Republicans, and a commission chair chosen by the House and Senate members of the Fulton County legislative delegation. North Fulton party activists like Hans von Spakovsky, who chaired the Fulton GOP in the 1990s before working for the George W. Bush Justice Department, were instrumental in devising vote-suppression strategies like voter ID laws and stoking fears of widespread vote fraud to justify tightening access to the ballot. Given the demographic balance of Fulton County, it’s difficult to imagine that Republican electoral strategies would not involve significant efforts to shrink the electorate.

These legislative proposals, if successful, would constitute a strong Republican play for power in Fulton County, and one to which observers of urban and metropolitan affairs in the rest of the country should pay attention. They signal another instance in a changing relationship between local governments and the states. While policy historians have devoted valuable attention to the relationship between city hall and Washington, D.C. during the relatively brief heyday of liberal social policy, the consequences of federal retreat from urban policy have more recently come into focus. When it comes to taxation, social services, political representation, transportation, schooling, and any number of other significant metropolitan policy issues, the state houses, and partisan politics at the state level, are becoming more and more consequential.

In Georgia and elsewhere, efforts to undercut the power of urban centers and black voters living in them is old news. The state’s County Unit System prevailed until the 1960s, promoting a “rule of the rustics” in which tiny rural communities routinely undercut state support for infrastructure in Atlanta, hamstrung efforts to secure home rule for the city, and gerrymandered legislative districts to keep black candidates out of state and federal office. Yet, this situation is something quite different–the use of state power as a tool in an intrametropolitan conflict. Unlike the era of rustic rule, this redistricting attack on black Democratic political strength originates within Fulton County’s own legislative delegation. The state House and Senate members who represent Fulton County constituents are supporting a plan that runs contrary to the apparent political preferences of a healthy majority of the county’s voters.

Understanding why this has happened requires a bit of discussion about how it has happened. Some aspects of this situation are unique to Georgia. The era of rustic rule in Georgia valorized the county boss and demonized urban governments. State legislatures in Georgia were thus historically stingy about granting home rule power to the cities; preserving control for the rural-dominated General Assembly over Atlanta’s affairs was a check on racial moderation and other forms of urban degeneracy real and imagined. The consequence of this tight grasp of power was that the legislature was potentially overburdened with consideration of any and all changes to local laws and policies. The compromise that emerged was the “local courtesy” system, in which legislation pertaining to local affairs is largely handled by the delegation of the affected county, which is effectively a gatekeeper to the whole Assembly. Georgia has 159 counties, by far the largest in proportion to state population in the nation. Insofar as most of the counties remain small, rural, and homogenous, the system works reasonably well. But it breaks down miserably for heavily urbanized, diverse, and internally differentiated counties like Fulton. In these settings, and particularly in the Atlanta metro area where suburban settlement spans several counties, control of a legislative delegation is a matter of immense importance and potentially of intense conflict.

After the dismantlement of the County Unit System in 1966 led to reapportionment of the legislature, significant numbers of black Democrats joined the larger Fulton County delegation, and were, until 2005, successful in stopping efforts to incorporate cities in the north Fulton areas of Sandy Springs, Johns Creek, and Milton, which were major goals of north Fulton residents (mostly Republicans) who had come to resent the use of their taxes to fund both public works and social services in the rest of the county. The Fulton delegation was also successful in preventing any consideration of legislation to amend the state constitution to allow north Fulton to secede (the number of 159 counties is a constitutional provision).

As north Fulton’s affluence made it a key territory for the state Republican Party, and the priorities of north Fulton Republicans increasingly revolved around secession, it was inevitable that the growing supermajority of Republicans would seek to remove the local courtesy roadblock by the tried and true method of gerrymandering—redistricting the northern Atlanta suburbs so that more seats crossed Fulton County’s borders with Cobb, Cherokee, Gwinnett, or Forsyth–all prime territory for suburban Republicanism. Thus, the 2013 legislative session opened with a Fulton delegation tilted by 13-12 toward the GOP in the House, 7-4 in the Senate, and Lynne Riley, an active member of the conservative American Legislative Exchange Council, newly elected as its chair.

Redistricting the Fulton County Commission is an example of the kind of change that would typically require preclearance from the Justice Department under Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, because Fulton County is a “covered jurisdiction”; the county’s history of racial vote suppression subjects it to federal review of any changes in its voting procedures, and it would not require a particularly loose interpretation of the VRA to attribute this redistricting to an effort to diminish minority power. It so happens that current Georgia Attorney General Sam Olens is a cosigner for Shelby County v. Holder, a suit pending before the United States Supreme Court that would invalidate Section 5 and free previously covered jurisdictions to change their voting procedures at will, with the burden falling on minority voters to prove an adverse effect on their voting rights after the fact. Before becoming the AG, Olens was the chair of the county commission in Cobb County, the catchbasin for tens of thousands of whites who fled Atlanta as the city desegregated in the 1960s and 1970s. Olens is thus firmly within the orbit of suburban Georgia Republicans for whom districting and voting are particularly salient.

So, the dominoes appear to be lining up for a series of interlinked efforts at protecting white north Fulton voters’ power. First, redistrict to create a virtually un-losable seat for another Republican on the Fulton County Commission. Then, wait for the Roberts Court to invalidate Section 5 of the VRA so that the new districting can take effect. Third, stack the Fulton County Election Commission with operatives committed to tightening minority access to the ballot, and, ultimately, bet the house on that one key race for Commission chair. Some of these dominoes seem pretty likely to fall (including, unfortunately, the demise of Section 5 at the hands of the Supremes), and others more farfetched (actually winning that commission chair election). And, from the point of view of north Fulton residents, encouraging a racially polarized campaign for the commission chair entails substantial risk. It could spark a backlash at the ballot box in the form of high turnout from south Fulton, and could result in the election of a commission chair with political debts to south Fulton (and grudges against north Fulton). Wouldn’t this reproduce the sort of polarized and dysfunctional government, dominated by the south and oppressive toward the north, that the north Fulton cohort have been bemoaning all along?

I think that’s the entire point.

Lynne Riley, the current chair of the Fulton County legislative delegation, is a north Fulton Republican who served as a County Commissioner from 2004 to 2010. As a protege of Karen Handel, she was committed to shrinking the scope of Fulton County government. And, at the same time as she was serving as a Fulton County Commissioner, Riley served as a member of the Milton County Legislative Advisory Commission convened in 2007 by state House members Jan Jones and Mark Burkhalter to advance the cause of county secession. It strains credulity to imagine that this effort is a good faith effort to fix county government. The proposal is virtually guaranteed to worsen polarization on the commission, and its chief sponsor was working to dismantle the county even as she was cashing a paycheck as one of its commissioners. Rather, it seems that north Fulton Republicans are making a short play to control the county and hedging with a longer game: if it doesn’t work out, it will only prove that the county is irredeemable, and that north Fulton demands for secession are justified.

After all, Riley’s Fulton delegation is also floating HR 275, another attempt to amend the state constitution to allow the secession of north Fulton, which doesn’t suggest a strong commitment to the success of county reorganization. If reforming Fulton County government fails on the terms that most of the public would recognize, i doubt most north Fulton Republicans would mind.

Let me say this again: when it comes to redistricting Fulton County as an ostensible good government measure, FAILURE, NOT SUCCESS, IS THE GOAL.

And if my account sounds conspiratorial, you could take House Speaker Pro Tem (and another co-sponsor of both HB 171 and HR 275) Jan Jones’s word for it:

“My goal is not to re-create Milton County. My goal is to end Fulton County and bring government closer to the people,” she said. “But it will take convincing.”

The great thing about redistricting is that it can dramatically reduce the amount of convincing your side needs to do.